Introducing FrozenDB

To make apple pie from scratch, you must first invent a database to store your recipes. – Carl Sagan

Well Carl (and avid readers), let me introduce you to FrozenDB. This is my twist on a single-file database, with the requirement that it operates on append-only files. FrozenDB is not something for production, but a learning exercise. This companion post expands on some of the things I learned about append-only structures, and database mechanics.

Ripple effects of immutability

The main technical premise of FrozenDB is – what if the database were append-only? Once a byte is written, it can never be deleted, or modified. Let’s walk through some of the ripple-effects from this decision:

- Mutable data structures (such as a hashmap of indices for quick lookups) can’t be written to disk, since you would want to modify them later

- Things written to disk cannot know in advance what is going to go in the future, unless your file structure specifically carves out known space for future structures. Even if you have known future space, you can’t write to that space until you’ve written up any intermediate bytes (which are then frozen)

- In order to avoid data loss, you need to write things to disk when you know them. However, any write is permanent and thus needs to handle any other user action that would follow

- One benefit of append-only is that any number of readers can concurrently read from disk, up through the given file size, since those bytes will never change

- However, even if you can have consistent reads (at a byte level), that means that readers need to handle partial writes. A writer could be in the middle of writing 20k bytes, and the reader grabs the file size half-way in between the write. There won’t be any data loss, but the reader needs to properly handle this case

- It’s easy for readers to know when data is written to the database, just by using OS-level API’s to monitor when files are modified

- Duplicating data in the file system to get-around immutability concerns is possible, but a dumb solution to working around immutability restrictions. If an algorithm has an incentive to re-order or duplicate data, it would be better suited for a multi-file database solution. The single-file architecture makes this approach out-of-scope

Log-file-as-a-database

Putting this all together, and the solutions will naturally start to look like a write-ahead-log (WAL). A WAL is just a serialized record of actions to take. For a database like postgres, this WAL is then materialized into the actual database later. For example, the actions “Add row 1, Add row 2, modify row 1 to have color=red” would be a WAL. Then, the final materialized database would have two rows, with row 1 in the final state. This becomes complicated, extremely quickly, when you talk about transactions and consistency models. However, that is a problem for the materialized view to solve, not the WAL.

FrozenDB takes the idea of a WAL and asks a question: “What if the WAL itself was the database”? Can we be clever about the user actions in such a way that we don’t need to parse & materialize the whole log file to understand the data in it? Let’s start with this concept, and slowly add complexity to it in order to meet our requirements:

Our first log-file database

Let’s start with the most basic DB operations get(key), and insert(key, value) So, in this world each line of our file could be a row, and perhaps we can JSON stringify the data

{"key": "key1", "value": "row1Data"}

{"key": "key2", "value": "row2Data"}Inserts are trivial, which is good. Now let’s think about reads: In order to find “key2”, we need to read the file, split it by newlines, parse the JSON, and find the one with “key2”.

Adding transaction support

Now, let’s add on support for Begin() and then Commit(). The only rule here is that when we later call get(key) it should not return the value unless the row is part of a committed transaction. The simplest thing we could do would just to add some kind of new control type that signifies when a transaction starts:

{"action": "begin"}

{"action": "addrow", "key": "key1", "value": "row1Data"}

{"action": "commit"}

{"action": "begin"}

{"action": "addrow", "key": "key2", "value": "row2Data"}

and so far this is really starting to look like a WAL. So for now, we still need to read the whole file. Then, we need to parse the JSON and figure out the action type. If we’re looking for a row, we also need to find a subsequent commit action further down the logfile

Baby’s first binary search

So far, finding a key has required reading the whole file, JSON parsing each line, finding the key, and then searching for a commit. Worst case, we’re searching the entire database every time. Let’s say we wanted to make this faster, with the knowledge that the keys are actually UUIDv7 keys (so they have a timestamp), and let’s say for now that all timestamps are strictly ordered (no skew). We can do a simple binary search where we have start_index=0, end_index=length-1 and then search through the midpoint etc etc.

How do we find the length of the database? How do we find row at index 72? Right now, we can’t for several reasons:

- We don’t know how many lines there are in a file (that requires scanning the entire file, looking for newlines)

- Each line could correspond to a data row, or a user action (begin/commit)

- Each line has to be fully JSON parsed to figure out this action

which turns into “read the entire file”. And if we’re reading the entire file, then there’s no point of doing binary search. To fix this, let’s have two new requirements:

- Rows must be fixed width

- No “special” rows, all rows are data rows

and that gets you a format like this

before_action (1 byte) | key sizeof(uuid) | value (fixed) | after_action

B | key1 | row1Data | padding | C

B | key2 | row2Data | padding | N

N | key3 | row3Data | padding | N

Where B = Begin, C = Commit, and N = no action. We’ve introduced several things here, let’s go through them one by one: First off, instead of a separate row, with a different “action” for begin/commit, we’re adding these as flags to the data rows. The user must call Begin() before writing any rows, so when this happens, we write the B flag , but nothing else. Then, the user calls Insert(), which writes key1 and row1Data. Finally, the user either adds more rows (so there is no immediate after_action), or they Commit() that row, which causes us to write the C flag

Next we now have padding. We want to make sure that each row is fixed size. So far, the begin action, the uuid, and the after_action are all the same size. Only the data payload is potentially variable, so we’ll add padding bytes to reach the fixed size.

With these two things in place, now we’ve solved our indexing needs. We can get the number of rows by size / row_size. We can index into any row by index * row_size.

But we’ve introduced some other problems: Rows are no longer atomic. When you call Begin(), this starts a row. However, that row is now in a partial state for potentially a very long time. Any reader will need to detect this case and handle it appropriately.

Adding rollback support

One “fun” aspect about building a database is that you have to think about the details for these various abstraction layers. How do transactions work? What about nested transactions? For a database like postgres, transactions have a lot of implications. The consistency model of a transaction enforces what rows (and changes to those rows) are visible during a transaction, etc. For FrozenDB, a row cannot be modified after it is written, so we only have some very simple rules:

- All rows must be part of a transaction

- A row cannot be modified after creation, even when part of a transaction

- A row is not visible for querying before it is committed

- Transactions cannot be nested

- To enable virtual transaction support, savepoints are allowed, along with rollback-to-savepoint

Imagine if you have code that looks like this:

tx = db.BeginTx()

tx.AddRow("key1", "data1")

tx2 = tx.SubTx()

tx2.AddRow("key2", "data2")

tx2.Rollback()

tx.Commit()

Internally, this SubTx() code has nothing to do with the database itself. The application logic just translates “Create a SubTx” to “generate a savepoint”, and “SubTx.rollback()” to “rollback to the savepoint”. This, for example is how postgres works. If you spend a bit of time and think about it more, this is why sub-transactions are never multi-threaded. Not only are they not multi-threaded, but even within the single thread, you generally shouldn’t write to the parent transaction until the child is committed or rolled back. The savepoint logic doesn’t allow for that kind of weird nesting-of-inserts (nor would any pattern there make any real sense).

With that simplification out of the way, we need to mark a savepoint, and we also need to be able to rollback fully, or to just a savepoint. A savepoint could either be considered an after_action for the current row, or a before_action for the next row. A rollback is now an alternative to Commit() so that is also an after_action. Our new data structure now looks like this:

before_action (1 byte) | key sizeof(uuid) | value (fixed) | after_action

B | key1 | row1Data | padding | C

B | key2 | row2Data | padding | S

N | key3 | row3Data | padding | N

N | key3 | row3Data | padding | R1where we now have the after_action S = savepoint, and R1 = rollback to the first savepoint.

The final boss

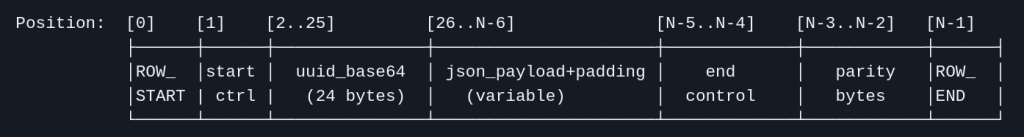

We’re pretty close to the final data structure that FrozenDB landed on. You can read the full file_format specification for more details. Things remaining to be added include checksum & data integrity requirements. It includes handling the scenario where the user does Begin() Commit() without any data insertion in between. It allows for clock skew, such that the keys don’t need to be strictly ascending in timestamp order (to help with things like client side delays and other processing ordering challenges). That being said, the final data row looks very close to what we have so far

With the following start control types:

| T | First data row of file, or after a transaction-ending command (TC, SC, R0-R9, S0-S9, or NR). Zero or one checksum rows may appear between the transaction end and the next T. |

| R | Previous data row ended with RE or SE (transaction continues). Checksum rows do not affect this rule. |

And the following end control types:

| Sequence | Meaning | State afterwards |

|---|---|---|

| TC | Commit | Closed |

| RE | Continue | Open |

| SC | Savepoint + Commit | Closed |

| SE | Savepoint + Continue | Open |

| R0 | Full rollback | Closed |

| R1-R9 | Rollback to savepoint N | Closed |

| S0 | Savepoint + Full rollback | Closed |

| S1-9 | Savepoint + Rollback to savepoint N | Closed |

| Null Row | No data | Closed |

Fuzzy binary search

The keys to my database are all timestamp-based uuids (uuidv7), and ordered. This allows binary search to detect whether a given key is present. For flexibility, I relaxed the ordering constraint. Given a clock_skew of 10ms, then the key being inserted is allowed to be up to 10ms older than the maximum timestamp seen. This constraint doesn’t affect our insert time, but let’s work through how it affects our search algorithm & performance.

Right away, we can see that this pushes our worst case time back to O(n). If every single key is inserted within the same e.g. 10ms clock skew, then there are no ordering guarantees for any of these keys. It will thus require us to search O(k) where k = number of keys in the clock skew. Perhaps if clients care, they can add throttling to inserts to bound this number.

With that out of the way, how does our binary search algorithm need to change? It’s pretty simple, we are just binary searching for any value within the clock skew. Then, we just need to linear probe to the left until we find the value, or the first key less than the clock skew. If not found, probe to the right until we find the value, or the first key greater than the clock skew.

Handling readers

One of the benefits, to counter the difficulties of an append-only structure is that concurrent reads are very simple. The concurrency challenges are not between readers and writers, but just to make sure that a reader is internally consistent when called from multiple threads. The consistency isn’t too hard to reason through either. The file size of the database will async increase as the database is written to. As long as the file size is maintained in a centralized place, then any part of the reader code can know what the current file size is as they do operations. If reader code needs to do things over a longer period of time, it can keep track of the file size when it started, and restrict reads up to that point (even if more data is available later).

An Appendix on appending my thoughts about append-only algorithms

My friend Will shared some examples on similar classes of algorithms, and I wanted to call a few of them out. The larger grouping is a bit obtusely named – Cache Oblivious Algorithms. There’s a nice paper which walks readers through some of these algorithms and what they’re trying to solve for. For database specifically, this presentation from Stony Brook walks through the challenges of minimizing disk I/O for a database and walks the reader towards cache oblivious algorithms to get there. Finally, we have Sorted String Tables as a primer into how this type of logic is done building up into LSM trees.

I suppose the main difference between FrozenDB and these other type of algorithms is they mostly allow for multiple append-only files. Once you have multiple files, you can essentially reorder and delete stuff over time in an amortized way. For example, consider how frozenDB allows for out-of-order writes, up to a clock skew. If we allowed multiple files, we could have a temp file, and then once the clock skew has passed, write the data in-order to a final file in order.

A similar idea, without the clock skew aspect would essentially be doing merge sort every 2^n size. Build up the current file, merge sort it with the previous, sorted file, and write the combined thing to disk.

I will note that FrozenDB isn’t ready to come anywhere close to a resource-intensive production tuning because none of the disk seeks are optimized. Either a cache-obvlivious algorithm, or a block-based solution from this section would need to be employed for any serious endeavor. But at that point, use something that is not just an exercise 🙂